VBAC: making a mountain out of molehill

**If you like information in an engaging movie format, I have two lessons on Supporting VBAC available in my Reclaiming Childbirth Collective, or as a Lesson Package, where I cover the content below and much more**

First, a bit of background. I'm using Australian statistics [1], but they are similar to other countries with medicalised maternity systems. The overall c-section rate is over 40% and rising year on year. This increase is primarily due to two main factors:

1. The high rates of induction for first-time mothers, resulting in c-sections (more than 50% of first labours are induced). Women who are induced have higher rates of c-section compared to those in spontaneous labour.

2. The low rates of VBAC. Only 21.8% of women who have had a previous c-section go into spontaneous labour. The vast majority of women have a repeat planned c-section (71.2%), and most c-sections are due to a 'previous c-section'.

However, these 'planned repeat c-section' statistics don't tell us how many women initially intended to have a VBAC – that data is not reported. Based on my experience and conversations, it is clear that many women are steered towards repeat surgery because of the ever-expanding reasons for induction (GDM, big baby, small baby, maternal age, term gestation, high BMI, etc.). Induction is usually discouraged with a uterine scar, so once a woman is labelled 'high risk', a repeat c-section is recommended.

The result of this all-encompassing 'risk' labelling is that the rate of VBAC women going into labour at the end of their pregnancy is low. This is unfortunate, since spontaneous VBAC labour is associated with a very good chance of a vaginal birth (up to 80% depending on the setting) [2]. Even obstetric guidelines recommend VBAC for 'low-risk' women. However, the obstetric definition of 'low risk' is extremely limited, and few women manage to remain in that category throughout their pregnancy.

The first step in supporting VBAC is supporting women to get to the point of spontaneous labour. The next step is supporting physiological birth. This post focuses specifically on the risk of uterine rupture during labour, because this is where the medical concern and fear-mongering is directed.

Uterine Rupture during VBAC

What is a uterine rupture?

Considering a rupture is the risk associated with VBAC, it is worth briefly describing what is involved. A uterine rupture can occur during any birth, even when no scar is present (particularly if syntocinon/pitocin is used). There are two types of uterine rupture:

-

Incomplete – the scar separates (dehiscence), but the outer layer of the uterus remains intact. Or the lower segment of the uterus becomes very thin at the site of the scar tissue (the 'window effect'). There are no symptoms, and most women and care providers will be unaware it has happened. This is the most common type of rupture.

-

Complete – the tear in the uterus extends through the entire uterine wall. It involves all three layers of the uterus and, typically, the broad ligament as well. It results in significant bleeding and threatens the life of the mother and baby.

Risk by numbers

Rate of uterine rupture during VBAC

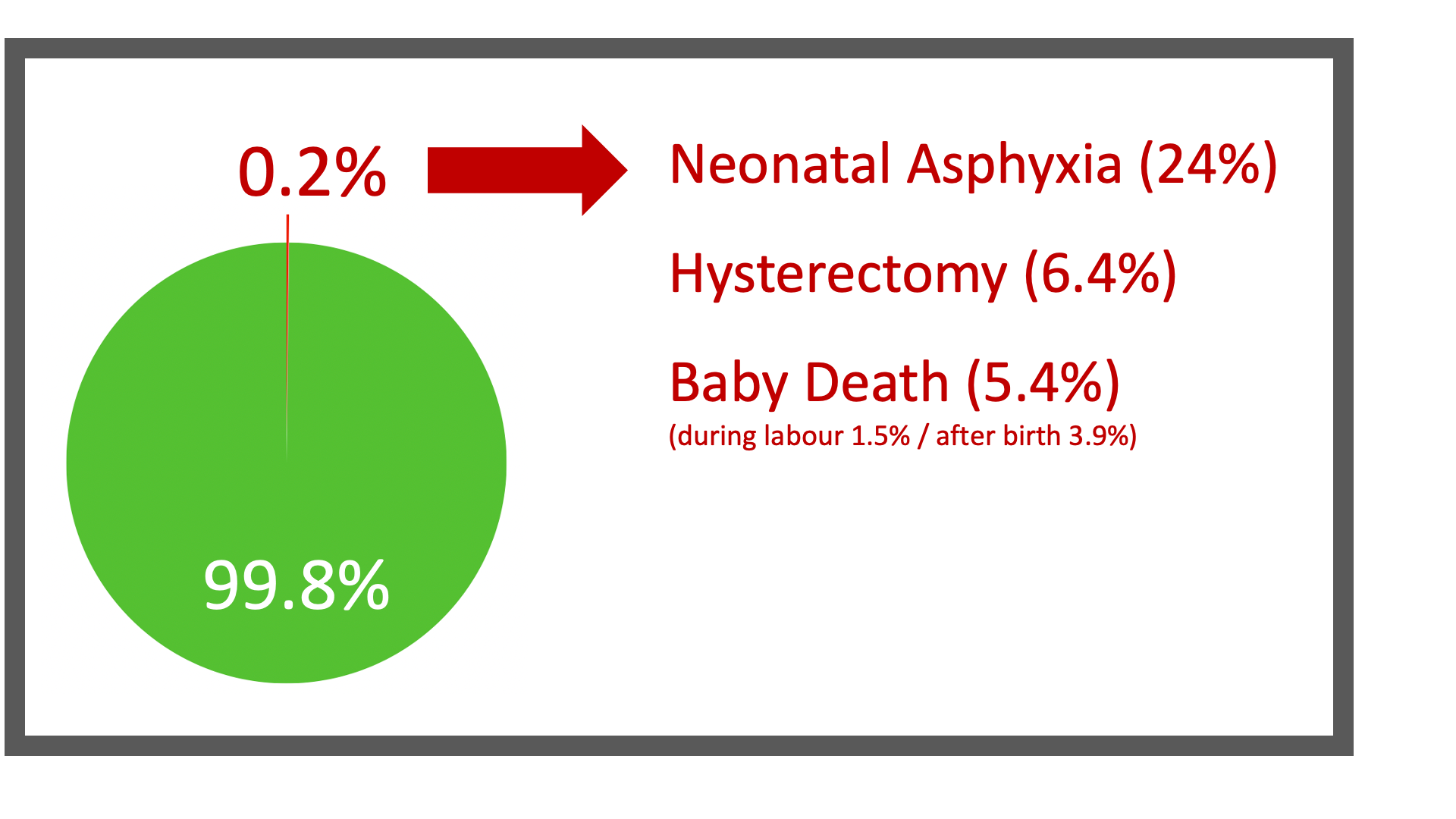

There are many ways of presenting numbers, and some methods may hold more significance for individuals than others. For example, if we look at the general rates of a complete uterine rupture during labour for a woman who has had one previous c-section. By 'general', I mean without considering factors that increase or decrease an individual's chance. The general rate of a uterine rupture [3] can be presented like this:

- 22 per 10,000 chance of uterine rupture

- 9,978 per 10,000 chance of no uterine rupture

- 0.2% chance of uterine rupture

- 99.8% chance of no uterine rupture

Or, visually, both of the diagrams below show 22 (red dots) per 10,000. In one diagram, the dots are together; in the other, they are spread out:

Care providers are required to share these general numbers and then discuss individual factors that increase or decrease the overall risk of a uterine rupture. For example, factors such as the inter-pregnancy interval [4], the type of scar [5], the number of previous c-sections [6], and interventions, including induction and augmentation of labour [7,8].

Of course, the chance of a uterine rupture occurring during labour can be eliminated by having a planned c-section instead. However, a repeat c-section comes with a higher overall complication rate and a greater risk of complications in any subsequent pregnancy [9].

Outcomes of a complete uterine rupture during labour

When considering VBAC risk, it is important to look not only at incidence but also at the outcomes for the 0.2% of women who experience a uterine rupture [3]. The most common outcome is an emergency c-section of a well baby. Around a quarter of babies will require resuscitation due to asphyxia (lack of oxygen). For a minority, a uterine rupture results in the loss of their uterus and/or baby

Risk Perception

Whilst the rates of uterine rupture are relatively small, humans don't perceive or assess risk objectively. We perceive risk emotionally, shaped by personal and social experience. A woman's own experiences and beliefs are the most influential factors in how she perceives risk and makes decisions, followed by the experiences and beliefs of her family and friends. You can present the same risk numbers to several women, and they will (should) make different decisions based on those numbers.

Care providers' perceptions of risk are also influenced by their personal experiences. When a care provider has been involved in a traumatic situation, it can be hard not to let that experience colour their perspective and approach. The memory of one uterine rupture will be stronger than all of the uncomplicated VBACs they may have seen. Obstetricians, in particular, regularly deal with the consequences of major complications because this is their area of expertise. They also miss out on witnessing physiological births, as this is the realm of the midwife and is rare in hospital settings. This can lead to fear-based counselling and practice. Care providers' perceptions of risk are also reinforced by institutional risk management:

Maternity services are focused on direct organisational risk. This means minimising the risk to the organisation from legal action, increased costs of care, or reputation... Long-term or individual risks are usually not part of the organisation's approach to risk assessment. Health issues that arise a long time after birth are difficult to clearly link back to the care provided during birth. In addition, emotional and psychological outcomes are difficult to measure, and are unlikely to impact the organisation. – Why Induction Matters

There is no escaping 'risk'. It's impossible to eliminate all risk from life (or birth), and every choice carries some level of risk. Women must choose the risk that feels most comfortable for them because there is no risk-free choice. The care provider's role is to share objective data and then support the woman's subjective decisions.

A Holistic Approach to Supporting VBAC

When I was a midwife, uterine rupture was the least of my worries when caring for a woman having a VBAC (and yes, my perception was influenced by my experiences). Whilst I had a professional obligation to discuss the numbers presented above, this was just one small part of sharing the map and nurturing self-trust during pregnancy (see my book if you don't know what these terms refer to).

Women planning a VBAC do need special treatment, but not in the form of disempowering, fear-based counselling or practice. They have often had a previous traumatic birth experience and are dealing with fear from family, friends, and the medical system, in addition to their own worries. They have been labelled 'high risk' and are constantly reminded of the potential disaster waiting to occur. Terms such as 'trial of labour' or 'trial of scar' are used to describe their plans for VBAC. They also risk 'failing' if they encounter any complications or end up having a repeat c-section. This impacts their ability to trust their body, follow their instincts and allow the physiology of birth to unfold. Often these women need more nurturing, reassurance and support from those involved in their birth. Not more monitoring, interventions and fear.

In my lessons on VBAC, I use the framework of childbirth as a rite of passage to explain how to support women and facilitate physiology during VBAC (this is risk management). I also discuss how holistic risk assessment and holistic observation can identify a uterine rupture should it happen. The lessons are an hour long, and I can't condense the information here. So, instead, here are some quick suggestions for supporting VBAC:

Pregnancy

-

Ask the woman about her previous birth experience and discuss what she needs from you for this birth.

- It is also important to consider partners and/or other family members who will be present at the birth. Often, the partner was present at the previous birth, which may have been traumatic to witness.

-

Present the 'risk' statistics in a number of ways, and find out what they (mother and partner) find most useful. Individualise risk and discuss factors that alter her risk profile.

-

Reinforce that she has a very good chance of having a vaginal birth if she is well supported. Overall, she has a greater likelihood of a vaginal birth than a woman having her first baby and no previous c-section.

-

Discuss factors that increase her chance of VBAC, eg, choosing a supportive care provider (and setting), and avoiding induced or augmentation.

- Talk to the woman and her partner about what actually happens if the uterus ruptures. They may be imagining all kinds of horrific scenes, such as the baby bursting out of an exploding abdomen. Additionally, discuss how a uterine rupture would be identified and managed.

- Explain how having a c-section after labour has started has benefits compared to a planned c-section with no labour. The baby is able to initiate labour and make the physiological changes needed for life outside the uterus. They will also be less likely to experience respiratory distress and require special care. In addition, both mother and baby will have labour hormones that assist with bonding. Even if she chooses a repeat c-section, she can insist on going into labour first.

-

If she is worried about 'failure', reassure her that she doesn't need to tell anyone she is planning a VBAC. She can say she's not sure and will decide in labour.

-

If she is planning to give birth in a hospital, she needs to know what the hospital policies are and decide what she will or won't go along with. This means discussing the risks associated with standard interventions, such as CTG monitoring and vaginal examinations. It may be helpful to research the VBAC rates at the hospital to get an idea about how supportive they are likely to be. A clearly worded birth plan can help communicate the woman's wishes to the staff.

- Talk about the possibility of her pregnancy going beyond the prescribed 'due date'. This is often a feature of VBAC pregnancy. Some hospitals or midwives consider this to be a risk factor. However, the risk of uterine rupture during labour is no greater.

- Talk about the emotional benefits of VBAC. Well-supported VBACs that centre the woman are usually healing and empowering for a woman and her partner, even when they result in a c-section.

-

Encourage her to talk to other women about their experiences of VBAC, read birth stories and watch VBAC birth movies.

-

Do not use disempowering language such as 'trial of scar' or constantly refer to her birth as a 'VBAC'. She is a woman having a baby, not a disaster waiting to happen.

Labour and birth

The care of a woman having a VBAC is no different to that of any other woman in labour, ie, facilitating an environment that supports physiology and promotes instinct. A registered care provider is expected to assess well-being and observe for signs of a uterine rupture: unusual pain, unusual contraction pattern, fetal heart rate abnormalities, unusual bleeding, a change in maternal observations, etc. However, those symptoms would be concerning in any labour, so this is not a different type of care. In addition, if a woman is unmedicated and connected to her body/baby, she will usually be the first to notice a problem. Any clinical assessments must be conducted with the woman's consent, and she can decline all or some monitoring.

My experience is that women having a VBAC can have additional psychological needs relating to their previous birth experience. For example, they may request vaginal examinations, particularly if their c-section was for 'failure to progress' (aka failure to wait). Even with information about how poor VEs are at indicating progress, they may want that dilation number (some non-VBAC women do too). They may also want more frequent fetal heart rate auscultation to 'reassure' them that the baby is well. Women having a VBAC, and even more so their partners, often need more reassurance and a birth attendant who believes in them. Of course, some women don't need or want any of this and choose birth without a care provider.

Is homebirth a safe option for VBAC?

Homebirth is often discussed in terms of safety, but no birth setting is entirely without risk. Different risks are associated with different options. In a hospital, there is a greater risk of unnecessary intervention and related complications. At home, if you are the 0.2% and need to transfer, there is the risk of more severe complications due to a delay in medical intervention. However, a delay may also occur in hospitals out of hours when theatre staff are not on site.

Based on my own experiences and those of midwives practising outside of hospitals, holistic observation is easier at a homebirth. You know the woman, her birth partner and her environment. She is in her own territory and behaving instinctively. You can focus on her behaviour and her contraction pattern without the distraction of the clinical setting. In research of uterine ruptures (carried out in hospitals), the first sign noticed by care providers is usually a change in the fetal heart rate. However, in the anecdotal experiences of homebirth midwives, uterine rupture is commonly identified due to an unusual contraction pattern. Then a transfer to the hospital occurs before fetal heart-rate changes.

Unfortunately, one of the risks of VBAC is being unable to get the support you want for a homebirth. Homebirth is not recommended or supported by hospital-based public homebirth services. Even in private midwifery, there is a lot of misinformation about VBAC. But, to be clear, private midwives in Australia can and do attend VBAC homebirths. This may change once the regulation of midwifery by medicine is complete, and there are already more hoops to jump through than when I used to attend homebirths. Women also have a legal right to freebirth or have an unregistered care provider attend their VBAC homebirth. The laws relating to freebirth are about the care provider's role, not the woman's choice. The law varies across states, but generally, an unregistered care provider is prohibited from 'practising midwifery' (and what that constitutes is very grey).

Summary

A VBAC is simply a birth. The most likely outcome of going into spontaneous labour after a previous c-section is the vaginal birth of a healthy baby. If we stop making a mountain out of a molehill, and instead nurture self-trust and support physiology, more women will experience VBAC as a healing and empowering rite of passage.

Further Resources

You can find more information on this topic in my Reclaiming Childbirth Collective or the Supporting VBAC Lesson Package.

Related blog posts

References

- Australia's mothers and babies report

- RANZCOG (2025) Birth after caesarean clinical guideline

- Vandenberghe et al. (2019) The International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems study of uterine rupture

- Adily et al. (2025) Inter-pregnancy interval and uterine rupture during a trial of labour after one previous caesarean delivery and no previous vaginal births

- Special Scars - list of studies

- Tahseen & Griffiths (2009) Vaginal birth after two caesarean sections (VBAC-2)

- Dekker et al. (2010) Risk of uterine rupture in Australian women attempting vaginal birth after one prior caesarean section

- Zhang et al. (2021) Oxytocin use in trial of labor after cesarean and its relationship with risk of uterine rupture in women with one previous caesarean section

- RANZCOG (2021) Caesarean section information leaflet

Join my mailing list to receive a monthly newsletter containing updates, evidence-based information, musings, rants and other goodies.

You will be sent a confirmation email. If you don't see an email from me in your inbox, check your junk folder and mark my email as 'not spam'.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.